Shamanic Daoyin Exercises for Health

Shamanic daoyin exercises used also in healing and divination, were the Neolithic precursor of today’s contemporary qigong (a.ka. chi kung).

According to the Chinese, qigong has existed since the beginning of time when Huang Di (Yellow Emperor), the first emperor ruled China more than four millennia ago. This was China’s Golden Age, a veritable Asian Atlantis, if you will.

Huang Di was considered an enlightened emperor, very skilled in martial arts and knowledgeable in healing and herbalism.

It is said he and his physician worked together to create the Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine) upon which the principles of Chinese medicine were founded.

Huang Di traditionally represents the epitome of Chinese civilization and culture and is also credited with many inventions. While his wife is said to have taught the Chinese to weave silk into clothing, he himself is said to have created the wheel, ships and carts, music, money, bricks and astronomy.

Most of the stories that circulate about him are the stuff of legends, but unfortunately, legends aside, very little is known about this shamanic period. Writings that make reference to this time were published at much later points in history.

Closer to the truth is that this was a period when people were known to treat various ailments with stone needles (the beginnings of acupuncture), and to cultivate health and longevity with shamanic daoyin exercises (the beginnings of qigong).

The Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine) is a manual that established the foundation on which principles of Chinese medicine still operate to this day.

This ancient text is traditionally attributed to Huang Di; however, historians have since dated this manual to a much later period in history (the Han Dynasty)

It is this Classic that mentions qigong as a method for healing, in addition to using bian shi (stone probes) as an acupuncture tool for manipulating people’s circulation of energy.

The unearthing of stone needles and inscribed tortoise shell relics point to the practice of Chinese medicine as far back as the Neolithic era (3,500-1,500 B.C.E.).

These and ancient images of shamanic gymnastic exercises known as daoyin that are found scattered throughout China, suggest that qigong did indeed originate some five to seven thousand years ago.

Evidence further suggests that early human civilization used shamanic dances to commune with nature and aid in healing and divination.

Over time, people came to believe that by imitating the natural movements of animals, combined with breathing techniques, (See Abdominal Breathing and Other Breathing Techniques) and mental concentration, they could promote certain physical and mental states of well-being and health.

Shamanic Dances & Stone Probes for Healing

T he discovery of a Neolithic vessel in Northwest China during the 1980s provides evidence of qigong being practiced for the purpose of healing and shamanic rituals

he discovery of a Neolithic vessel in Northwest China during the 1980s provides evidence of qigong being practiced for the purpose of healing and shamanic rituals

Inscribed on the vessel was an image of wuxi, a priest-shaman engaging in meditative and gymnastic postures to reach a trance-like state of ecstasy.

Other artifacts dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1766-1154 B.C.) have also been found, notably the Jia Gu Wen (Oracle Bone Scripture).These tortoise shell inscriptions, numbering more than 160,000 pieces are the earliest evidence of the first written word in Chinese ideography. Inscriptions on these shells are mostly of a religious shamanic nature.

However, eighteenth century B.C. Shang dynasty bones give testimony to an ancient practice of stimulating “acupuncture reflexes” to adjust misaligned balances of chi.

Also, stone probes known as bian shi were used to stimulate cavities or strategic points on the energy channels which affected the flow of chi. Stimulating these points would readjust the energy circulation and relieve pain.

These artifacts suggest that ancient Chinese already understood that sharp tools worked better than fingers in stimulating the chi.

While Chinese legends tell of shamanic tribal members imitating the movements of wild animals

in dances to counteract rheumatism, arthritis, and other ailments arising from a cold damp environment, other indigenous cultures around the world also share a history of communal shamanic healing dances.

What distinguishes shamanic practices in China from these counterparts is not only the extended use of these exercises from the dawn of civilization and their subsequent continued survival, but also its continuous development and use to this day.

Further Evolution of Daoyin Exercises

Another important source of reference is the I Ching, also phonetically written Yi Jing (Book of Changes). Some historians date this book as far back as before 2400 B.C. while others suggest that it was written before 1122 B.C.

Evidence suggests that several authors from different historical periods contributed to the making of this book.

Evidence suggests that several authors from different historical periods contributed to the making of this book.

More significantly is its reference to shamanistic ideas and beliefs that existed long before the book came into existence, the discussion of chi, and the integration of three natural powers: Tian (Heaven), Di (Earth) and Ren (Man).

Studying the relationship of these three energies enabled the Chinese to make predictions about what might happen around them.

The natural forces were represented by eight trigrams that combined into a total of sixty-four hexagrams, representing all the variations of nature and its dynamic form. Understanding the relationships was the first step in qigong development.

As practitioners deepened their understanding of the origin, function, purpose and flow of the vital energy, qigong gradually evolved from a simple shamanic dance to more specific methods of movement, breathing and concentration.

These shamanistic daoyin exercises were utilized to cure various ailments, promote health, develop physical stamina and increase longevity.

Bamboo and bronze records produced between 1100 B.C. and 221 B.C. during the Warring States of the Zhou dynastic reign, describes specific exercises on breathing. (See Abdominal Breathing and Other Breathing Techniques).

At this point, qigong had evolved with several theories on energy cultivation, including nourishing San Bao Three Treasures of the human body: chi or vital energy, jing or life essence and shen or spirit.

Early Development of Chinese Medicine

This period saw rapid development of the basic principles from which traditional Chinese medicine developed, including Yin-Yang theory, Five Elements, different diagnostic tools and methods of healing, notably acupuncture, herbs, qigong and diet.

Physicians began to map out the channels through which chi flowed, and developed laws and principles of how the energy should move.

Several medical references written between 221 B.C. and 220 A.D. during the Qin and Han Dynasties, discussed the use of breathing techniques to promote chi circulation.

One such book was the Nan Jing (Classic on Disorders) written by Bian Que, a physician who prescribed breathing to promote circulation.

The Xing Qi Ming (Circulating Qi Inscription), written between 475 B.C. and 206 B.C. also gives textual evidence of meditative daoyin practices during the Warring States Period of the Zhou Dynasty.

Other textual evidence included Han Shu Yi Wen Zhi (The Han Book of Arts and Scholarship) which described four methods of shamanic daoyin training, and Zhou Yi Can Tong Qi (A Comparative Study of the Zhou Dynasty Book of Changes) by Wei Bo-Yang who compared the shamanic relationship of human beings to natural elements and chi.

Other textual evidence included Han Shu Yi Wen Zhi (The Han Book of Arts and Scholarship) which described four methods of shamanic daoyin training, and Zhou Yi Can Tong Qi (A Comparative Study of the Zhou Dynasty Book of Changes) by Wei Bo-Yang who compared the shamanic relationship of human beings to natural elements and chi.

Around 300 B.C., Taoist philosopher Chuang Tzu (also phonetically spelled Zhuang Zi) suggested that “The men of old breathed clear down to their heels, thus confirming the breathing method employed for circulating the chi at the time.

Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu, (also phonetically spelled Lao Zi) described in his 6th century B.C. classic Tao Te Ching or Dao De Jing (The Virtue of the Way), breathing techniques for prolonging life, as well as merging with Nature. Zhuan qi zhi rou suggested that by concentrating on the chi one could achieve stillness.

These early Confucian and Taoist philosophical writings were not religious in nature. Instead, they described breathing techniques and gymnastic daoyin exercises for the purpose of promoting health and extending life.

Both the Qin (221-207 B.C.) and Han Dynasties (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) saw rapid growth in medical skills. This furthered the growth of daoyin theory and practice. Dissection of bodies helped to further the knowledge of human anatomy, energy channels and nervous systems.

Daoyin, the Predecessor of Modern Qigong

In 3 A.D. physician Hua Tuo used acupuncture for anesthesia in surgery. He taught the Taoist Juan Ju daoyin method of circulating chi and he created his own qigong method that is still practiced today, called Wu Qin Xi or Five Animal Play.

Hua Tuo prescribed this set of exercises to treat arthritis, rheumatism, digestive disorders, nervous afflictions and problems with circulation.

Another contemporary medical scholar, Zhang Zhong-Jing, also contributed to the development of qigong. His book Ji Gui Yao Lue (Prescriptions From the Golden Chamber) teaches about chi optimization through daoyin breathing and gymnastic exercises, acupuncture, moxibustion and massage.

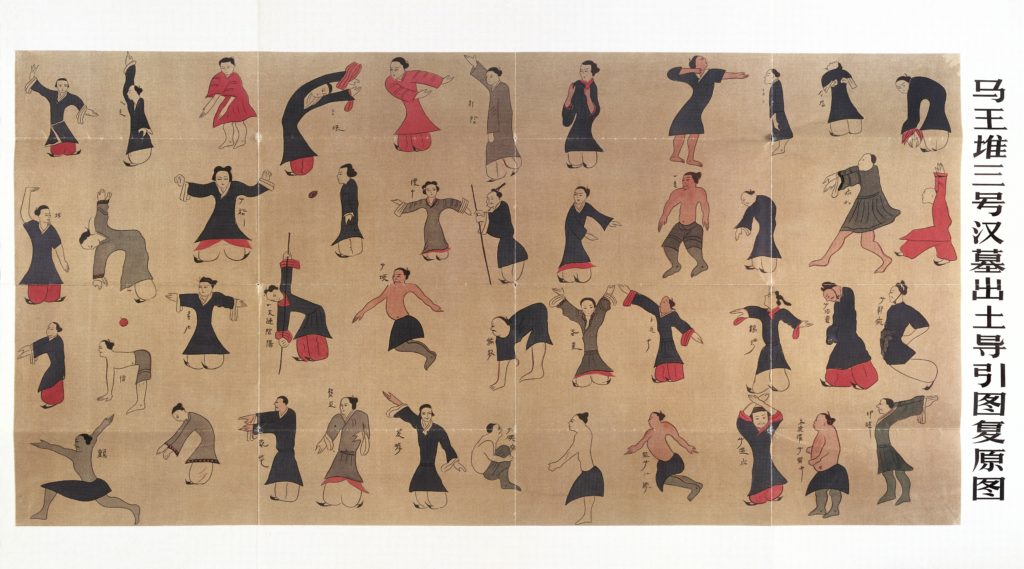

Perhaps one of the most significant archeological findings to date are the shamanic artifacts unearthed in 1984 in the Han Dynastic Ma Wang Dui Tombs in Changsha, Hunan Province.

One of them is a silk book called Que Gu Shi Qi Pian (Abstaining From Cereal and Consuming Chi) that teaches fasting, taking herbs and practicing breathing exercises.

The second artifact is a silk painting dated 168 B.C. during the Western Han dynasty, called the Daoyin Tu (Daoyin Gymnastics Chart). Measuring approximately 100 centimeters by 50 centimeters in length, it featured some of the earliest drawings of daoyin postures.

The 44 gymnastic postures were drawn in color in four rows of eleven figures each, featuring men and women, peasants and nobility, and people of all ages, giving the suggestion that these daoyin exercises were not restricted to any one social stratum of society.

In addition to the daoyin drawings were commentaries on the purposes intended for each exercise. These sketches were divided into two major categories: imitative animal play and cures for various ailments.

The animal plays included movements of wolf, monkey, ape, bear, crane, hawk and vulture. The cures were purportedly for deafness, hernia, anxiety, knee pains, neck problems, abdominal boating, sciatica, fever, and pneumonia.

Also discovered in 1984 is the Daoyin Yin Shu (Bamboo Strip Book) dated 186 B.C. of the Han Dynasty. This detailed manuscript outlines a set of principles for health and longevity to be practiced daily according to the different seasons of the year:

Forty sets of exercises and techniques specifically aimed at promoting longevity, forty-four sets to cure disease, twenty-four sets for therapy and prevention, and three sets of breathing techniques corresponding to the four different seasons to promote health and longevity.

In short, daoyin exercises probably evolved from shamanic healing dances during the shamanistic period of early Chinese civilization. These gymnastic exercises combined with breathing techniques and concentration became what is now known as qigong.